BUNCHE, ESMERALDAS

The visit was coordinated by Fernando Godoy, director of the Fundación de Desarrollo Social (social development foundation) based in Atacames. On the way to Bunche we stopped in the beachtown of Muisne. We arrived by motorboat since all access roads are not anymore. Señor Clemente Paneso, acting priest when the padre cannot make it from Muisne, had picked us up from Macará to escort us home. His sister in law, the unique Carmen, was to be our minder and landlady. She and a busy Paneso became tireless guides to many activities.

We were lucky to arrive the same day as the town celebrates their patron saint, San Jacinto. A new statue carved in Cuenca was to replace the old and well loved wooden saint, and it was scheduled to arrive that day. In the afternoon the procession arrived by boat. San Jacinto was paraded through town by a large crowd who chanted rythmic hymns and escorted by drumming, before being taken to the church and placed along his predecesor, who now had an uncertain future. A musical service was offered for the reception. So Bunche launched into a few days of celebration. Preparations included "la minga", a communal cleaning of streets and public spaces. We walked up the hills to some beautifull waterfalls in the Aguacate river, a place which is to become Bunches’ fresh water supply point to replace the salty wells in town. On the way, Paneso and Gringo taught us about native plants and their uses; the hard as ivory Tagua palm seed, the palm frond that is bleached and softened to make the famous Panamá hats in Manabí, the coastal Balsa wood, the multipurposed Chonta palm, wild fruits like Obos (small wild plums), Pepa de pán (breadfruit), Guava verde (large beanlike pod), to name a few.

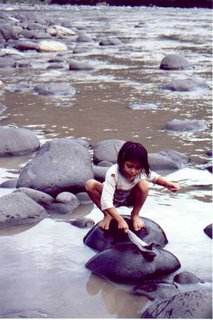

Also walked along the beach to visit the neighbouring fishing town of Cabo san Francisco. Then, a simple task as going to get some fresh water, a scarce comodity in the coast, from a stream became an odyssey. With the rising tide we jumped in a dugout canoe, filled it with empty containers and put our safety in the hands of Pila, a 10 year old selfmade jack of all trades. After about 2 hours we found the probervial spring, disembarked and stocked up on the vital fluid.

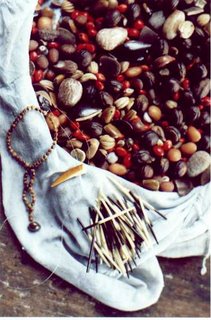

During our stay we had conversations with a few buncheanos about some pressing matters. There is the well known problem of prawn farming. Large areas of mangrove, which used to be habitat of some of the staples in Bunches’ diet (Concha, Cangrejo, Jaiba, various species of fish), have been transformed into ponds to raise the expensive crustacean. Now, due to a virus affecting it, half the ponds are empty of Camarón, or any other dweller. On top of this, some people think the chemicals used in the farms are filtering through into the remaining healthy ecosystems. Another setback are the plagues destroying cash crops these people used to depend on (Coconut, Cacao, Coffee, Banana). Causes are unclear but the results are felt. Health is another issue, a health centre needs to be finished to house permanent staff and store medical supplies, and hopefully a much needed pathology unit on site. Our last evening we had a meeting with the Comité Pro-mejora de Bunche (local improvements comitee) to discuss our stay and some initiatives the community is working on, such as an experimental Concha (seashell) farms. Concha harvest is a prime activity and has been overexploited, so now some areas have been set aside to protect it.

Despite all the obstacles and isolation, Bunche knows how to have a good time, and our last night we spent partying in the name of San Jacinto in the main square. We danced to the sounds of cumbia, salsa and ballenato, ate ceviche de concha and calamari, and gulped the old sugar cane rum. The next morning before departure, we attended the baptism of 11 children. Then boated it back to Muisne, together with the priest, who was a long way from his home, India.

MACARÁ, ESMERALDAS

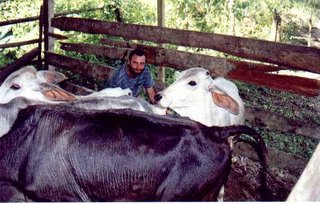

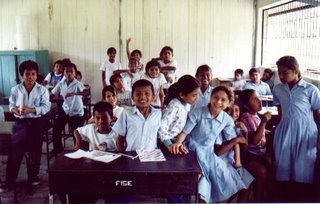

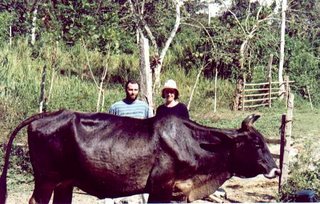

In this peacefull rural community, about half an hour from the coast and 1 hour south of Atacames, we arrived to the Angulo-Basurto family. In the primary school of the recinto we met with teachers and some mothers, who officially welcomed us into the community. After the meeting we spent time with the children, teaching english and talking, and had a walk around the community meeting some of the locals. Also in store was a visit to a finca (farm), where we could see different races of cattle (Criollo Brahman and Holten), the skins of tigrillo and nupa snake, cacao and pea plantations, harvested some toronja (grapefruit), learnt about mambla timber (used in construction molds) and had a swim with river prawn.

As far as food goes, a regional speciality widely eaten is the chamé, seemingly a fish, but must be part amphibian since it can last for days out of the water. Apparently, due to the disease currently affecting prawn farms, the ponds are being used to farm chamé instead. Our hosts supplement their income transporting chamé inland where it’s hard to come by. Not due to the fish, but to a previous condition, one of us got a bout of severe diarhea, which didn’t last long under sra. Nildas care and nursing knowledge. The next day we returned to the school to do some planting of ornamentals outside the child care centre. After this we rushed off to support the local soccer team, who fought fiercely to resist the onslaught of the opposite team. The event was well organized and had a good turnout. Then, it was off to visit the parroquia of Tonchihue, a nearby seaside town that lives of fishing, and do some shopping for our last nights’ dinner.

In all, Macará felt like a relaxed and friendly place, it’s people generous and extroverted as coastal character goes. Of interest are some clay artifacts the family had found by the river, after flooding exposed new soil profiles. Apparently they are found very often in the area and are probably sold to anyone who pays for them. It would be of use for the community to protect this cultural heritage and create a museum as an alternative to the poaching for example.

Tbased in Atacames, Eshe stay in the village was possible thanks to arrangements made by don Fernando Godoy, the director of Fundación de Desarrollo Social, a social and development foundation Esmeraldas.

LOS TAYOS, PASTAZA

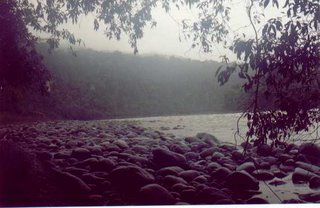

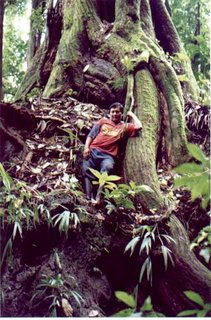

Aproaching the village of Chuwitayo, about 2 hours drive from Puyo, gave us an idea of the work activities in the area. Cattle raising, sugar cane cultivation and logging seem to be the main occupations. Ocassionally an ecotourism sign on the roadside. From Chuwitayo it was about a 3 hour hike through muddy terrain but the surrounding landscape was what took our breath away. Walking along the rushing Pastaza river, flanked by tall limestone escarpment, covered in old growth tropical forest, made the trip already worthwhile.

During the stay we walked to nearby limestone caves, where a migrating bird nests for a few months of the year. The collection of Tayo chicks used to be an important economical and cultural activity for the Shuar people. It provided them with meat and plenty of fat, reputedly with curative properties. Now the species is in danger of extintion, so this practice has become very limited. There were impresive views of the river and jungle below from a couple of lookouts. Luís is hoping to receive council aproval to implement a track over a preexisting one and through virgin forest, to complete a circuit back to the village, thus encompassing a variety of landscapes.

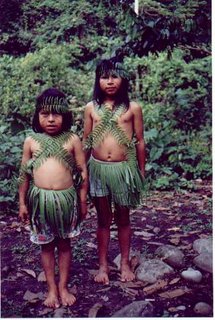

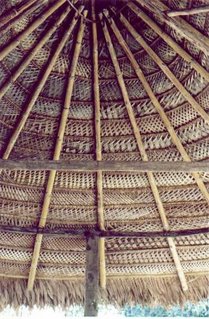

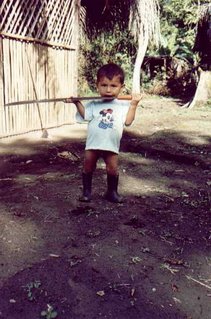

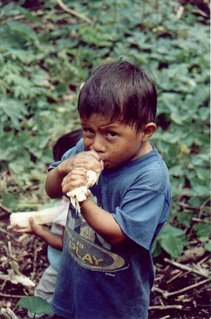

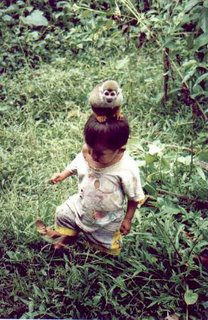

An absolute highlight was sharing with this warm family, learning about medicinal and ceremonial botany, usefull timbers, prechristian Shuar beliefs, social customs, dances and songs, crafts and festivities (Chonta fest). Their diet consists mainly of a handfull of crops they cultivate and sporadic hunting. We ate lots of rice, plátano verde y maduro, papa china (a tuber), yuca in all it’s incarnations (soup, fritters, chicha) fish from the river, cooked inside large leaves together with palmitos (palm heart), concha (river snails) and the tastiest humitas (corn parcels).

Swimming, Puro Puyo, conversations on how to dispose of rubbish, harvesting and planting crops, bats, vampires, huge glow beetles, a natural musical soundtrack to go to sleep and fun times with the Caniras added to an enriching experience; invaluable is to partake with a group of indigenous people keen to preserve their ancestral traditions and environment, making a sustainable living while resisting the pressire of more destructive practices. Special thanks to indigenous run Papangu-Atacapi Tours travel agency, affiliated to O.P.I.P. (organization of indigenous peoples of Pastaza) for coordination and contacts.

PHOTOS

CUEVA DE LOS TAYOS EN PASTAZA

Comments